The era of simply plugging solar panels into the grid and walking away is over. As Europe’s energy transition matures, Southeast Europe is adopting a more sophisticated strategy - one that values reliability as much as sustainability.

For the past decade, renewable energy investment in the Balkans was straightforward, driven by Feed-in Tariffs (FiTs) that shielded developers from market forces. This led to a “land grab” of rapidly deployed, subsidized capacity. Now the region is entering a new phase: shifting from sheer capacity deployment to system integration, market-based dispatch, and delivering firm (on-demand) power. In the Western Balkans, this evolution is accelerated by EU accession requirements and the urgent need to decarbonize a power sector long reliant on lignite.

Crucially, the key question is changing from “How much power can you build?” to “When can you deliver it?”. This marks the rise of a Green Baseload approach focused on around-the-clock dispatchable green energy.

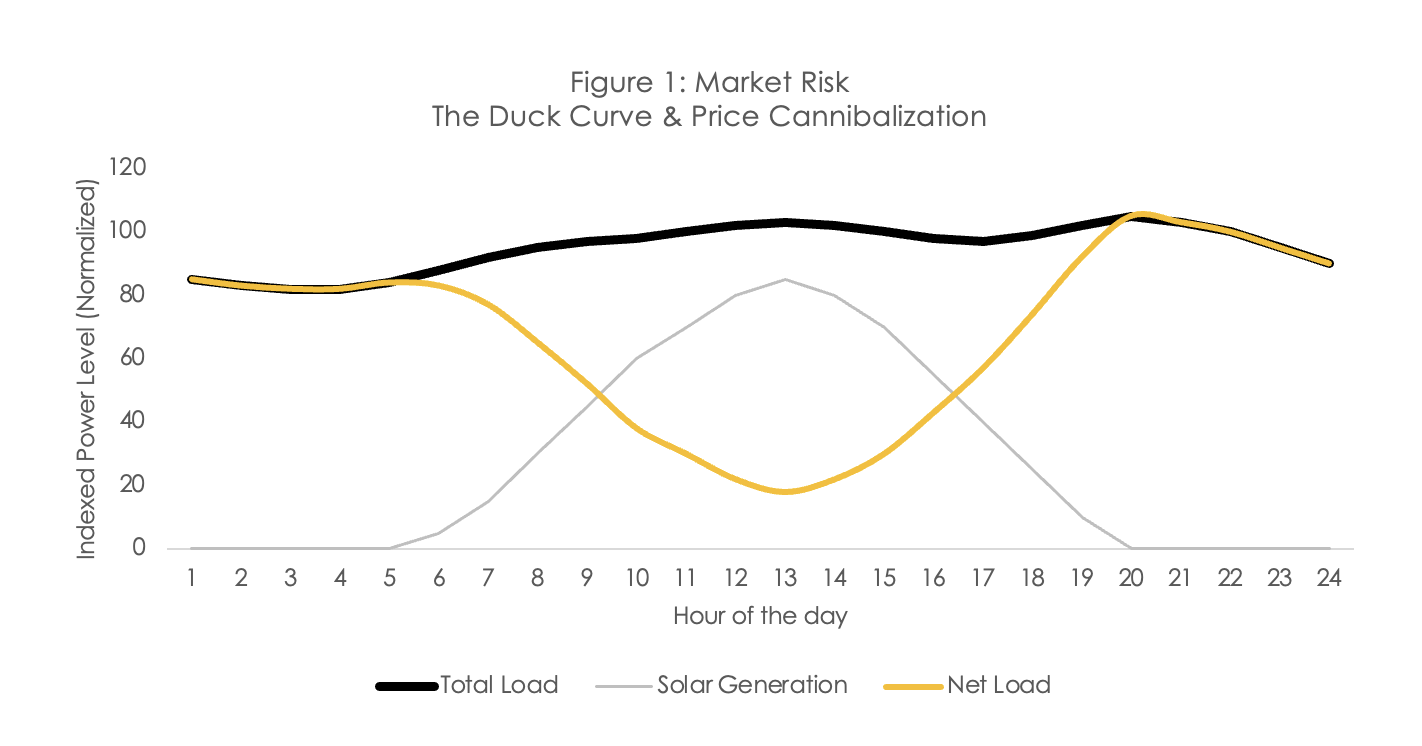

As more variable renewable energy floods the grid, the value of each intermittent kWh is dropping. This effect, known as price cannibalization, occurs when wholesale electricity prices collapse during periods of peak renewable output.

For solar-only projects, this trend is especially problematic. They suffer a “revenue valley” in winter months when output is low but demand (and prices) is high. On a daily scale, solar generation follows a midday bell-curve. As solar penetration rises, midday net load falls (the famous “duck curve”), causing daytime price dips and steep price spikes in the evening. In short, a pure-solar strategy is increasingly exposed to volatile prices and eroding revenue.

As solar penetration rises in the Balkans, the grid faces a structural “duck curve” where midday net load collapses, driving wholesale prices toward zero or negative territory. Conversely, demand ramps steeply in the evening when solar is offline. This volatility creates a risk for standalone solar assets but creates a premium for flexible generation capable of shifting volume to high-value peak hours.

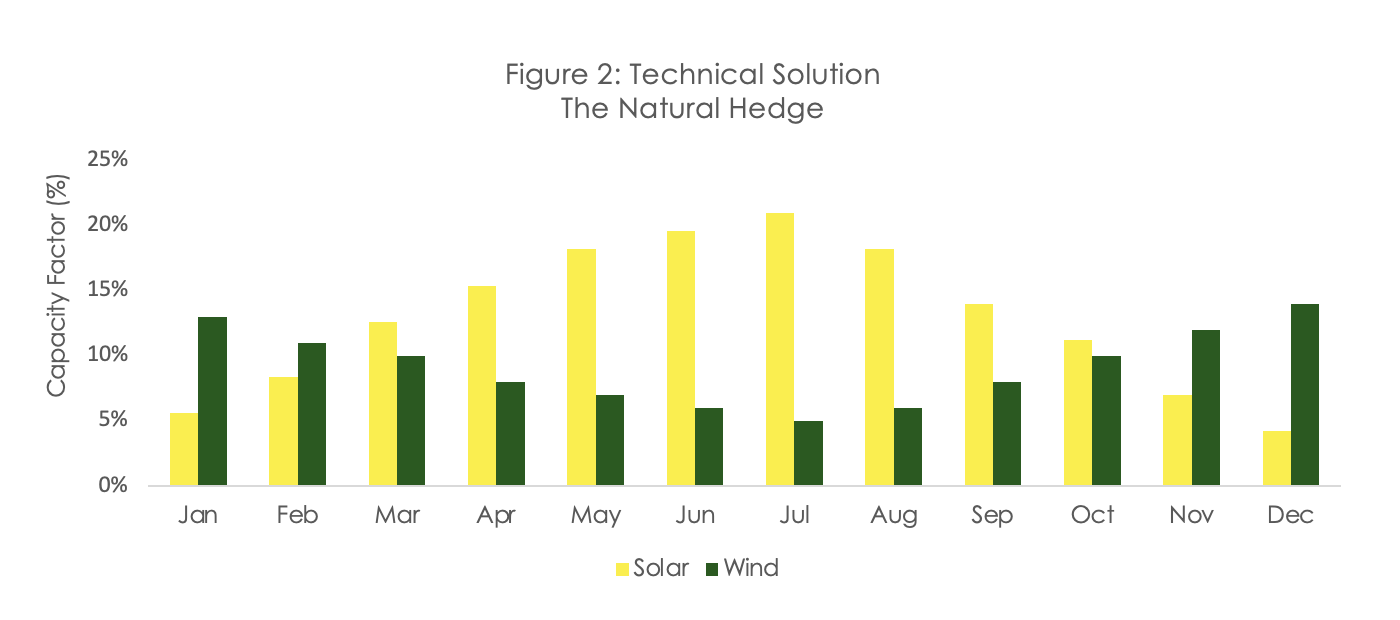

In the Western Balkans, nature itself provides part of the solution. The region’s climate offers a built-in hedge: solar and wind resources are negatively correlated. Solar irradiance peaks from May through August, where as wind (for example, Serbia’s strong Košava wind) blows hardest in late autumn, winter, and early spring. When solar output wanes, wind often surges, and vice versa.

This complementarity allows for a strategic blend of assets. By pairing roughly 1.4 units of solar for every 1 unit of wind, a hybrid portfolio creates a natural hedge that smooths out monthly generation and revenues. Wind output typically rises in late afternoon and continues overnight, offsetting the evening drop-off of solar and mitigating the duck-curve effect. In essence, each resource fills the other’s gaps to provide a steadier, more reliable power supply.

Figure 2 illustrates the structural complementarity of the portfolio resources. While solar capacity factors (yellow) peak during the summer months, the region’s specific wind corridors (green) drive maximum production during the winter. This counter-cyclical correlation naturally smooths the annual output profile, mitigating the “winter revenue valley” typical of solar-only assets and increasing the portfolio's effective base load factor.

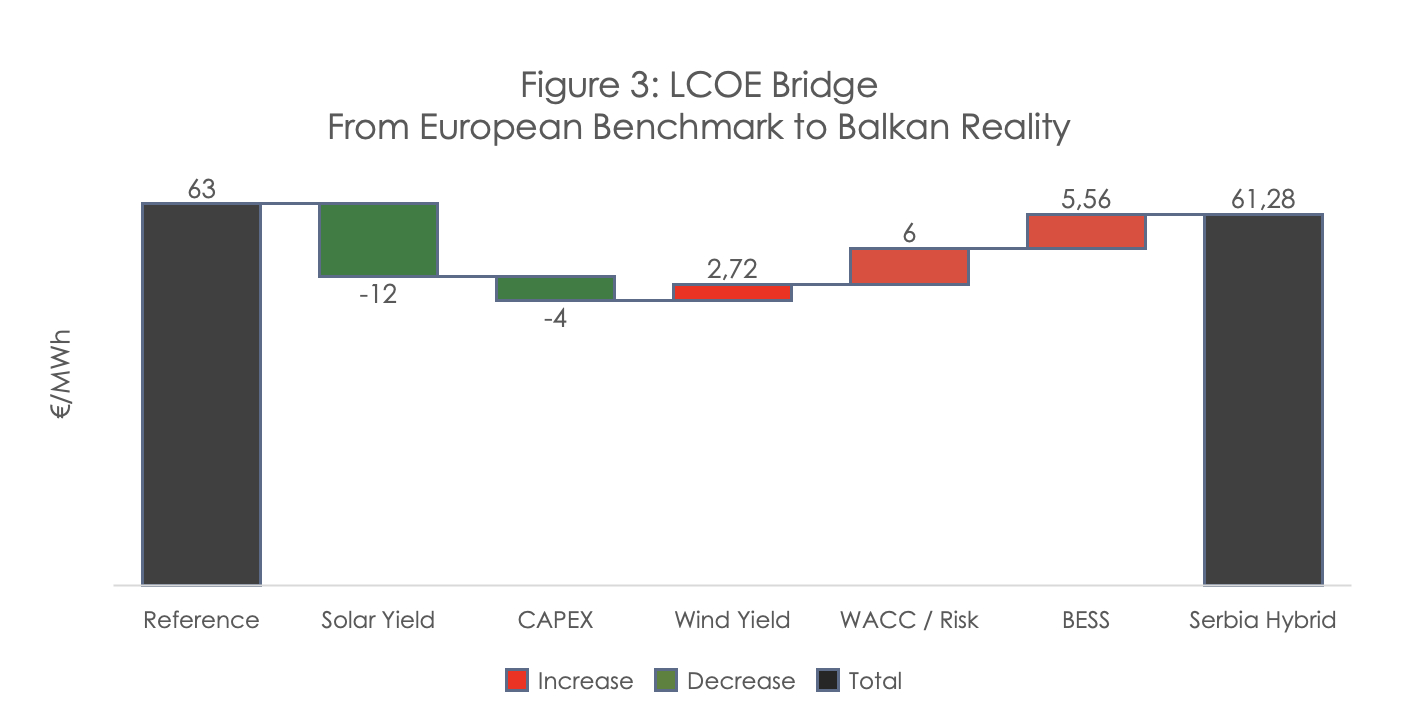

Let’s be realistic: solving intermittency costs money. A standalone solar plant might boast a lower LCOE (often <€50/MWh), but it generates power when it is least valuable. Moving to a "Green Baseload" model inevitably lifts that cost base - wind turbines and batteries simply cost more to build than solar panels.

However, Figure 3 reveals acritical advantage. It demonstrates that while we incur premiums for storage and capital, the Balkans' exceptional solar yield and lower Balance of System costs (civil works, labor, and land) act as a natural subsidy. These structural savings bring our firm, hybrid LCOE down to ~€61/MWh - a price competitive with standard European wind assets.

Is this higher than basic solar? Yes. But the goal isn't to be the cheapest, but to be the most valuable. In a market where midday solar prices are crashing toward ~€40/MWh, paying a moderate cost premium to build a system that captures nearly double that price in the evening is just good business. The logic is simple: a slightly higher LCOE is worth it if it guarantees you aren't selling into a price crash.

Figure 3 illustrates the cost competitiveness of the Serbian portfolio. Starting from a standard European benchmark, we observe that the region's superior solar irradiation (-€12.0/MWh) and lower Balance of System costs (-€4.0/MWh impact) create a massive initial cost reduction. These savings successfully absorb the premiums required for the lower local wind yield (+€2.72), higher regional financing rates (+€6.0), and battery integration (+€5.56). The result is a firm, hybrid product at ~€61/MWh, effectively matching the cost of intermittent wind projects elsewhere in Europe.

Hybridization also unlocks efficiency gains. One is “cable pooling”, designing the grid connection below the combined peak capacity of the solar and wind components. Because peak sun and peak wind rarely coincide, a 1.7 GW solar-wind portfolio might only require about a 1.2 GW grid interconnection. This significantly cuts capital costs for substations and transmission infrastructure.

Another key enabler is battery storage. Importantly, the hybrid model doesn’t rely on extremely long-duration storage. Instead, Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) are sized for short-term, high-value tasks (roughly 1-2 hours of capacity) such as grid balancing and firming up output. The primary role of the BESS is “commercial firming” - managing supply-demand imbalances to avoid punitive penalties and smoothing out ramp rates to maintain grid stability.

This strategy is tailor-made for the Western Balkans’ energy economy. The region is retiring old coal plants and suffers from volatile hydropower output, leading to a shortage of flexible, on-demand generation. Simultaneously, heavy industries (steel, cement, copper) are bracing for the EU’s incoming CBAM, which will impose tariffs on carbon-intensive exports. These companies urgently need 24/7 low-carbon electricity to remain competitive. A Green Baseload supply that guarantees round-the-clock clean power can command a premium in this environment.

Cross-border market integration further boosts the viability of hybrid projects. The expansion of a regional power exchange (e.g. the Alpine-Adriatic Danube Power Exchange, ADEX) links the Balkans with EU electricity markets. This connectivity enables producers to export surplus green power to neighboring high-demand markets (such as Hungary) and to arbitrage between the hydro-dominated Balkan grid and the thermal-dominated Central European grid. In short, stronger interconnection ensures that excess renewable energy can find profitable demand beyond the local grid.

The “Green Baseload” strategy is emerging as the logical next step for renewable energy in the Western Balkans. By combining generation sources and storage, it directly addresses the three major challenges in the sector: intermittency, grid congestion, and price cannibalization. While the hybrid model entails a higher LCOE, it delivers superior risk-adjusted returns by protecting the capture price and unlocking premium revenues in an increasingly interconnected European power market.

As European power markets mature, the question is no longer how much green capacity can be built, but which projects can reliably deliver value across market cycles.

As the region transitions from capacity to deliverability, Systema Capital Partners is open to conversations with market participants, sponsors and capital providers looking to turn this thesis into bankable, investable projects.